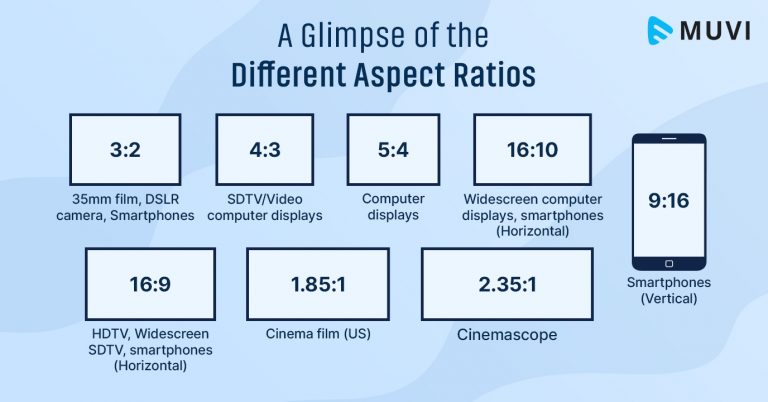

In the start of a 3-part blog series dealing with video/film topics, I’ve decided to start off with a fairly basic subject, and that is dealing with film and video aspect ratios, that is the ratios between the width and height of various forms of film and TV.

Originally film was in 4:3 (or 1.3:1) aspect ratio, that if the height is considered “1 unit”, the width is 1.3 units.

Modern Times (1936)

Early TV copied this, and is why that long running TV standard (“standard definition”) adopted the same 4:3 ratio.

Then in order to compete with TV, Hollywood invented the “Widescreen” aspect ratio with Cinerama, CinemaScope, and VistaVision.

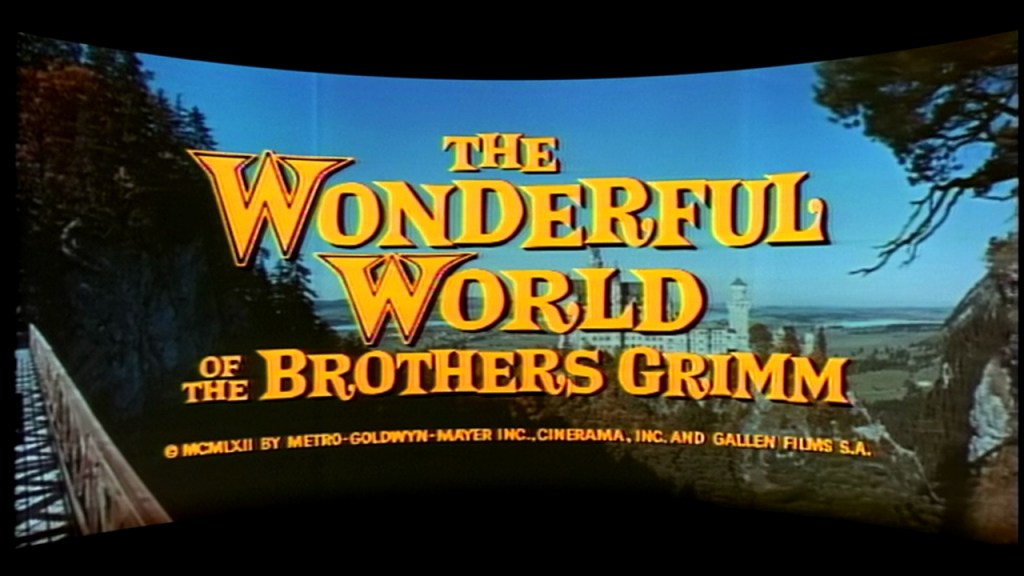

Cinerama was presented to the world in 1952, utilizing 3 rolls of 35mm film projected by 3 projectors onto an enormous curved screen, subtending 146 degrees of arc, ultilizing an aspect ratio of 2.59:1.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), Cinerama system.

In 1953 the president of 20th Century Fox, Spyros Skouras, had the head of Fox’s research department, Earl Sponable, devise a system to compete with Cinerama that would use standard 35mm film. He came up with the CinemaScope system which utilized an anamorphic lens to compress a wide image (2.55:1) onto standard 35mm film. Then a reverse lens on the cinema projector stretched it out onto the projection screen.

The Robe (1953), CinemaScope system.

In 1954, engineers at Paramount invented the VistaVision system, which didn’t use an anamorphic lens but instead ran the 35mm film horizontally instead of vertically through the cameras, yielding an aspect ratio of 1.66:1.

White Christmas (1954), VistaVision system.

Also in 1953, broadway producer Mike Todd and United Artists Theaters in partnership with The American Optical Company invented the Todd-AO process, which uses a 65mm film negative which is converted to a 70mm film positive, yielding a 2.20:1 aspect ratio.

Around the World in 80 Days (1956), Todd-AO system.

And in the 1950s Universal Studios backed the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, which is why it is also one of the cinema standard widescreen formats, slightly wider than 16:9.

And this leads into the world of broadcast TV. Here in the U.S., the NTSC (National Television Systems Committee) system was used for analog, standard definition broadcast TV. Utilizing a 4:3 aspect ratio (with 720 x 480 pixel resolution), it remained the norm for broadcast TV for years. In 1979, the Japanese public broadcaster NHK developed an analog High Definition TV system called Hi-Vision, with a 5:3 aspect ratio (and 1125 lines of resolution). Later, when digital High Definition was introduced, the 16:9 aspect ratio was chosen because it was close to the 1.85:1 aspect ratio of film (with 1280 x 720 and 1920 x 1080 pixel resolutions).

Gilligan’s Island (1964), SD

Game of Thrones (2011), HD

And the line is totally blurred of course, in that you have older TV shows that have had high-def Blu-ray releases, because they have gone back to the original film negatives and interpositives to scan the material in high definition, and of course presented with “pillar boxing” to be displayed on 16:9 TVs:

As a matter of fact, for the Lost in Space Blu-ray release they were able to go back to the original 35mm interpositives that were in 1.37:1 aspect ratio, which is actually slightly wider than the 4:3 aspect ratio that they were originally broadcast in.

And now with the rise of internet, newer formats have arrived. First and foremost is the “YouTube Short”/”TikTok” vertical format. Originally created by people who shot videos from their phones vertically either from laziness or lack of knowledge (just flip the phones 90 degrees, folks! 😃) and then posted them on the net, it of course has evolved into its own format, the world of 9:16 aspect ratio! 😉 And I’m fine with that, the media always adapts with the times and creates new ideas and artforms. There are even guides online for this type of content:

And there is also the square video format used on Facebook and other platforms like Instagram:

It’s a whole new world out there! I’ve had to adjust my thinking about all this new stuff. I’ve been so ingrained into having to produce videos that strictly adhere to broadcast standards that I’ve had to do a total mental adjustment in order to loosen my thinking. Which is actually a good thing. Let’s face it, as is often mentioned, the customer is always right. If a client wants me to produce TikTok videos, so be it. Likewise if they want the whole Abel Gance Napoleon or Stanley Kubrik 2001: A Space Odyssey Cinerama multi-projection immersive experience, bring it on! 😁

(This particular journey down the rabbit hole was inspired by a conversation I recently had with my brother, who runs the sound system company Encore Entertainment (encoresound.com), about the legacy (SD) Canon cameras that we still have. In my case the venerable Canon XL-1 and with him, the capable smaller sister, the Canon GL-1:

He said that he still uses the Gl-1 for recording gigs for bands that he does because he just posts them on his webpage and Facebook page, and I realized that that is totally fine. We are no longer bounded by the older constraints.)

Leave a comment